I’ve completed this and some other wargames before starting a blog, but I thought I should revisit them and do a proper walkthrough, and that would also help me organize my notes beyond one-liners that I no longer know what they were for :D So, going to start with Bandit, which is the most basic and beginner friendly of the OverTheWire wargames. You can look at each level’s page for a list of commands that you may need to solve it and some additional reading material that might help in better understanding what’s going on. I will also give man pages descriptions for the commands I’ll use to complete the levels.

Level 0

The goal of this level is for you to log into the game using SSH. The host to which you need to connect is bandit.labs.overthewire.org. The username is bandit0 and the password is bandit0. Once logged in, go to the Level 1 page to find out how to beat Level 1.

Level 0 –> Level 1

The password for the next level is stored in a file called readme located in the home directory. Use this password to log into bandit1 using SSH. Whenever you find a password for a level, use SSH to log into that level and continue the game.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

Well, this is straightforward. The required file just lies around for the reading

Useful command(s)

cat – concatenate files and print on the standard output

Level 1 –> Level 2

The password for the next level is stored in a file called – located in the home directory

Although filenames starting with dashes are legal in Linux, if you try to use some commands on them, the dash would get confused with command flags. If you try to cat it directly, cat will just wait for further input. The workaround is to feed cat the path to the file (can also be done just by using the current directory path)

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Level 2 –> Level 3

The password for the next level is stored in a file called spaces in this filename located in the home directory

Spaces in filenames can be interpreted wrongly on the command line, because they may look as separators for the commands instead of literal spaces that are part of a filename, and this leads to all sorts of problems. That is why using spaces in filenames are generally avoided in Linux. If you try to cat the file as it is, this is what happens:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

To solve the issue, you can either wrap the filenames in quotes or escape the spaces with backslashes, to ensure that the name of the file is passed correctly to the command (and if you use Tab completion, the shell will automatically escape them for you :D)

1 2 3 4 | |

Level 3 –> Level 4

The password for the next level is stored in a hidden file in the inhere directory.

If you do a normal ls, you won’t see anything. To see hidden files, you use the -a option, which stands for —all:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Useful command(s)

ls – list directory contents

-a, —all do not ignore entries starting with .

Level 4 – Level 5

The password for the next level is stored in the only human-readable file in the inhere directory. Tip: if your terminal is messed up, try the “reset” command.

1 2 3 4 5 | |

You can try to manually cat each of them, until you will reach the right one:

1 2 | |

But what if there were hundreds of files? If you use the file command, you can see the difference between the files:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

Now you know which file to look in for the password!

Useful command(s)

file — determine file type

Level 5 –> Level 6

The password for the next level is stored in a file somewhere under the inhere directory and has all of the following properties: – human-readable – 1033 bytes in size – not executable

Well, clearly no manual work here, the directory is filled with other folders:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

To find the file with the required properties, we can use..find! It conveniently has the exact switches for what we’re looking for:

1 2 3 4 | |

Useful command(s)

find – search for files in a directory hierarchy

-executable Matches files which are executable and directories which are searchable (in a file name resolution sense).

-readable Matches files which are readable.

-size n File uses n units of space. `c’ for bytes

Level 6 –> Level 7

The password for the next level is stored somewhere on the server and has all of the following properties: – owned by user bandit7 – owned by group bandit6 – 33 bytes in size

Again, find comes to the rescue!

1 2 3 4 | |

Useful command(s)

find

-user uname

File is owned by user uname (numeric user ID allowed).

-group gname

File belongs to group gname (numeric group ID allowed).

Level 7 –> Level 8

The password for the next level is stored in the file data.txt next to the word millionth

We can use grep to get the line with the millionth word and our password:

1 2 | |

Useful command(s)

grep searches the named input FILEs (or standard input if no files are named, or if a single hyphen-minus (–) is given as file name) for lines containing a match to the given PATTERN. By default, grep prints the matching lines.

Level 8 –> Level 9

The password for the next level is stored in the file data.txt and is the only line of text that occurs only once

To get only the unique line(s), we will use some more pipe redirection:

1 2 | |

Useful command(s)

sort – sort lines of text files

uniq – report or omit repeated lines -u, —unique only print unique lines

Level 9 –> Level 10

The password for the next level is stored in the file data.txt in one of the few human-readable strings, beginning with several ‘=’ characters.

For this one we can use strings and grep for the = sign:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

Useful command(s)

strings – print the strings of printable characters in files.

Level 10 –> Level 11

The password for the next level is stored in the file data.txt, which contains base64 encoded data

Luckily, there is a command-line utility just for that purpose!

1 2 | |

Useful command(s)

base64 – base64 encode/decode data and print to standard output

-d, —decode decode data

Level 11 –> Level 12

The password for the next level is stored in the file data.txt, where all lowercase (a-z) and uppercase (A-Z) letters have been rotated by 13 positions

If you read the ROT13 Implementation section on Wikipedia, it will actually give you a hint on how to solve this challenge and the program needed.

1 2 | |

Because the content of the file has been rotated 13 characters, we use the tr command to shift it back to the original

Useful command(s)

tr – translate or delete characters

CHAR1-CHAR2 all characters from CHAR1 to CHAR2 in ascending order

Level 12 –> Level 13

The password for the next level is stored in the file data.txt, which is a hexdump of a file that has been repeatedly compressed. For this level it may be useful to create a directory under /tmp in which you can work using mkdir. For example: mkdir /tmp/myname123. Then copy the datafile using cp, and rename it using mv (read the manpages!)

If you cat data.txt this is what you will see:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 | |

So, if it’s been repeatedly compressed, than repeatedly decompressing it should do the job (this actually took an annoying time of repetitions…am I repeating the repeat word too often? :D)

1 2 3 | |

To reverse the hexdump we will use xxd:

1

| |

Now let’s look at it (not literally, it’s full of garbage):

1 2 | |

So now we know the data file was previously a binary file and it’s been compressed with gzip. This means we know how to decompress it. There are a couple ways to do it. If you want to use gzip, you have to rename the file with a .gz extension:

1 2 3 4 | |

You can also use zcat directly on the file without adding any extension:

1 2 3 | |

Since we know the program used to compress it, we use the same for the reverse:

1 2 3 4 | |

We’ve been through this kind of decompression before:

1 2 3 | |

Next we have a tar archive and we will just loop decompressions until we’re done:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | |

Finally! Had enough decompressions for one day.

Useful command(s)

xxd – make a hexdump or do the reverse.

-r | -revert

reverse operation: convert (or patch) hexdump into binary. If not writing to stdout, xxd writes into its output file without truncating it.

mv – move (rename) files

gzip – compress or expand files. Whenever possible, each file is replaced by one with the extension .gz. By default, gzip keeps the original file name and timestamp in the compressed file. Compressed files can be restored to their original form using gzip -d or gunzip or zcat.

-d —decompress —uncompress Decompress.

zcat uncompresses either a list of files on the command line or its standard input and writes the uncompressed data on standard output. zcat will uncompress files that have the correct magic number whether they have a .gz suffix or not.

bzip2 – a block-sorting file compressor

bzip2 expects a list of file names to accompany the command-line flags. Each file is replaced by a compressed version of itself, with the name “original_name.bz2”.

If the file does not end in one of the recognised endings, .bz2, .bz, .tbz2 or .tbz, bzip2 complains that it cannot guess the name of the original file, and uses the original name with .out appended.

-d —decompress Force decompression.

Tar stores and extracts files from a tape or disk archive.

-x, —extract, —get extract files from an archive

-v, —verbose verbosely list files processed

-f, —file ARCHIVE use archive file or device ARCHIVE

Level 13 –> Level 14

The password for the next level is stored in /etc/bandit_pass/bandit14 and can only be read by user bandit14. For this level, you don’t get the next password, but you get a private SSH key that can be used to log into the next level. Note: localhost is a hostname that refers to the machine you are working on

Ok, we have a private key:

1 2 3 4 | |

The description hinted that we need to use the private key to SSH as bandit14 and read the password, and also mentioned localhost. So let’s ssh to localhost:

1 2 3 | |

Useful command(s)

ssh — OpenSSH SSH client (remote login program)

-i identity_file Selects a file from which the identity (private key) for public key authentication is read.

Level 14 –> Level 15

The password for the next level can be retrieved by submitting the password of the current level to port 30000 on localhost.

This level is straightforward since we have netcat available:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Useful command(s)

The nc (or netcat) utility is used for just about anything under the sun involving TCP, UDP, or UNIX-domain sockets. It can open TCP connections, send UDP packets, listen on arbitrary TCP and UDP ports, do port scanning, and deal with both IPv4 and IPv6.

Level 15 –> Level 16

The password for the next level can be retrieved by submitting the password of the current level to port 30001 on localhost using SSL encryption.

Helpful note: Getting “HEARTBEATING” and “Read R BLOCK”? Use -quiet and read the “CONNECTED COMMANDS” section in the manpage. Next to ‘R’ and ‘Q’, the ‘B’ command also works in this version of that command…

For this the openssl command line utility will come in handy:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

In particular, we will use the s_client command which is very useful for SSL servers testing and diagnostics. We use it to connect to localhost on the specified port:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

Without the -quiet flag we would get a ton of information and instead of the password we would see some HEARTBEATING and read R BLOCK messages

Useful command(s)

openssl – OpenSSL command line tool

s_client This implements a generic SSL/TLS client which can establish a transparent connection to a remote server speaking SSL/TLS. It’s intended for testing purposes only and provides only rudimentary interface functionality but internally uses mostly all functionality of the OpenSSL ssl library.

-connect host:port This specifies the host and optional port to connect to. If not specified then an attempt is made to connect to the local host on port 4433

-quiet inhibit printing of session and certificate information. This implicitly turns on -ign_eof as well.

More information (along with the CONNECTED COMMANDS section) can be found on https://openssl.org/docs/apps/s_client.html#options

Level 16 –> Level 17

The password for the next level can be retrieved by submitting the password of the current level to a port on localhost in the range 31000 to 32000. First find out which of these ports have a server listening on them. Then find out which of those speak SSL and which don’t. There is only 1 server that will give the next credentials, the others will simply send back to you whatever you send to it.

Fortunately, we have nmap installed, so scanning the port range is easy!

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

Using netcat to probe all those ports, I found out that ports 31518 and 31790 use SSL from the following error:

1 2 | |

The rest of the ports just echo back what you send them. So now let’s feed the password to these ports and see which one will give the answer:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

So, port 31518 just returns the string you give it. Must be the other one:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 | |

Instead of a password we got a SSH private key. I copied it in my .ssh folder, gave it right permissions to stop the WARNING: UNPROTECTED PRIVATE KEY FILE! message, and used it to log in as the next level and get the password:

1 2 3 4 | |

Useful command(s)

nmap – Network exploration tool and security / port scanner

-p

: Only scan specified ports Ex: -p22; -p1-65535; -p U:53,111,137,T:21-25,80,139,8080,S:9

Level 17 –> Level 18

There are 2 files in the homedirectory: passwords.old and passwords.new. The password for the next level is in passwords.new and is the only line that has been changed between passwords.old and passwords.new

NOTE: if you have solved this level and see ‘Byebye!’ when trying to log into bandit18, this is related to the next level, bandit19

We can use the diff program to see the differences between the 2 files:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

The 42c42 string means that line 42 in the first file was changed to line 42 in the second. diff uses some characters to signify the kind of change that was found:

1 2 3 | |

The number to the left of the character represents the line number in the first file, while the one to the right refers to the line number of the second file. So the correct password is kfBf3eYk5BPBRzwjqutbbfE887SVc5Yd

Useful command(s)

diff – compare files line by line

Level 18 –> Level 19

The password for the next level is stored in a file readme in the homedirectory. Unfortunately, someone has modified .bashrc to log you out when you log in with SSH.

Upon logging in, we are instantly disconnected and get a bye message:

1 2 | |

The way to run a command immediately after logging in is to add it after the ssh command:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

Level 19 –> Level 20

To gain access to the next level, you should use the setuid binary in the homedirectory. Execute it without arguments to find out how to use it. The password for this level can be found in the usual place (/etc/bandit_pass), after you have used to setuid binary.

1 2 3 4 | |

The binary is a setuid binary owned by the bandit20 user, which means we can use it to directly read he password as if we were bandit20. No exploitation needed!

1 2 | |

Level 20 –> Level 21

There is a setuid binary in the homedirectory that does the following: it makes a connection to localhost on the port you specify as a commandline argument. It then reads a line of text from the connection and compares it to the password in the previous level (bandit20). If the password is correct, it will transmit the password for the next level (bandit21).

NOTE: To beat this level, you need to login twice: once to run the setuid command, and once to start a network daemon to which the setuid will connect.

NOTE 2: Try connecting to your own network daemon to see if it works as you think

Here we will need to use 2 connections because we need to set up a listener as well. But since we have netcat, all is well! :D

1 2 3 | |

Have netcat listen on a port:

1 2 | |

Then use the setuid program to connect from a new shell to the netcat listener. We see on the netcat side the connection has been received and if we give it the password we will receive the next one:

1 2 3 | |

You can see on the other shell with the setuid binary that the password matched:

1 2 3 | |

Level 21 –> Level 22

A program is running automatically at regular intervals from cron, the time-based job scheduler. Look in /etc/cron.d/ for the configuration and see what command is being executed.

If we look in /etc/cron.d/ we see a bunch of files, we are interested in the cronjob for bandit22:

1 2 | |

So cron runs a shell script as the bandit22 user. Let’s see what it is:

1 2 3 4 | |

So the bandit22 user decided to paste his password in a random named file in /tmp/, but he gave everyone the permission to read it!

1 2 | |

Useful command(s)

cron – daemon to execute scheduled commands

A crontab file contains instructions to the cron(8) daemon of the general form: “run this command at this time on this date”. Each user has their own crontab, and commands in any given crontab will be executed as the user who owns the crontab.

The format of a cron command is very much the V7 standard, with a number of upward-compatible extensions. Each line has five time and date fields, followed by a command, followed by a newline character (‘\n’). The system crontab (/etc/crontab) uses the same format, except that the username for the command is specified after the time and date fields and before the command. The fields may be separated by spaces or tabs.

Commands are executed by cron(8) when the minute, hour, and month of year fields match the current time, and when at least one of the two day fields (day of month, or day of week) match the current time. cron(8) examines cron entries once every minute.

A field may be an asterisk (*), which always stands for “first-last”.

Level 22 –> Level 23

A program is running automatically at regular intervals from cron, the time-based job scheduler. Look in /etc/cron.d/ for the configuration and see what command is being executed.

NOTE: Looking at shell scripts written by other people is a very useful skill. The script for this level is intentionally made easy to read. If you are having problems understanding what it does, try executing it to see the debug information it prints.

Again, we identify the cronjob file first to know where to look further:

1 2 | |

This script is more involved than the last:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

So, this script assigns the current user name to the myname variable. We know that’s bandit22. And then copies the password to a file in /tmp/ that we have to identify. We can do this by substitution:

myname=bandit23 (that is what the whoami command will return)

Then the string “I m user bandit23” is fed to md5sum to compute a MD5 hash. You can check the output on your system:

1 2 | |

The cut command is used to print just the hash line:

1 2 | |

Now we know that mytarget=8ca319486bfbbc3663ea0fbe81326349

1 2 | |

Useful command(s)

whoami – Print the user name associated with the current effective user ID

echo – display a line of text

md5sum – compute and check MD5 message digest

cut – remove sections from each line of files

-d, —delimiter=DELIM use DELIM instead of TAB for field delimiter

-f, —fields=LIST select only these fields; also print any line that contains no delimiter character, unless the -s option is specified

Level 23 –> Level 24

A program is running automatically at regular intervals from cron, the time-based job scheduler. Look in /etc/cron.d/ for the configuration and see what command is being executed.

NOTE: This level requires you to create your own first shell-script. This is a very big step and you should be proud of yourself when you beat this level!

NOTE 2: Keep in mind that your shell script is removed once executed, so you may want to keep a copy around…

The beginning is the same as last levels:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

So this script executes and then deletes all scripts in the /var/spool/bandit24 directory. We can place a script of our own in there to copy the password of the bandit24 user in a location we have access to. I made a directory in /tmp/ first:

1 2 | |

Then I made a file that will hold the password later and gave it the most liberal permissions possible:

1 2 | |

Next, I made a script that will be executed by cron. It just copies the bandit24 password to the file I’ve created earlier.

1 2 3 4 | |

I gave my script super permissive rights, then copied it to /var/spool/bandit24 to be executed:

1 2 | |

Waited a bit, then profit:

1 2 | |

Level 24 –> Level 25

A daemon is listening on port 30002 and will give you the password for bandit25 if given the password for bandit24 and a secret numeric 4-digit pincode. There is no way to retrieve the pincode except by going through all of the 10000 combinaties, called brute-forcing.

1 2 3 | |

Meh, this means we’ll have to bruteforce the pincode and try until the daemon says it’s correct. I wrote a quick Python script for that:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 | |

And running it:

1 2 3 4 | |

Level 25 –> Level 26

Logging in to bandit26 from bandit25 should be fairly easy… The shell for user bandit26 is not /bin/bash, but something else. Find out what it is, how it works and how to break out of it.

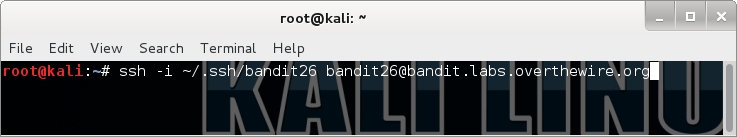

After logging in I found a SSH private key for level 26 just lying around:

1 2 | |

But when using it to log in, the connection closes immediately, after showing this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

After reading a bit about how to find out another user’s shell, what worked was looking in /etc/passwd for that specific user and checking the shell field (last one):

1 2 | |

Cool, we have something! Let’s look at it:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

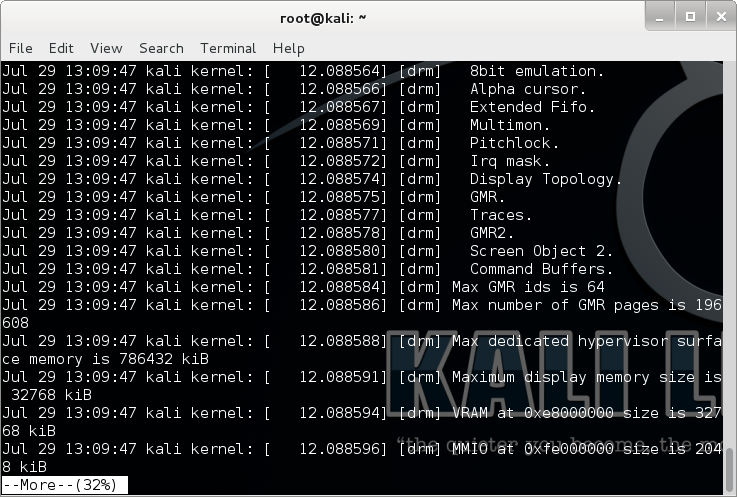

So this shell uses more to display the contents of the text.txt file. Since more only displays one screen at a time, we want to see what else is contained in that file, but we don’t have access to it, nor can we do anything about the shell. So the only way to proceed is to thoroughly read the more manpage and see if we can find something useful..

So, apparently it’s possible to start an editor from more, and that rang a bell because vi was listed among the commands that might be needed to solve this level. And then maybe we can see inside the file some more (see what I did there? xD)

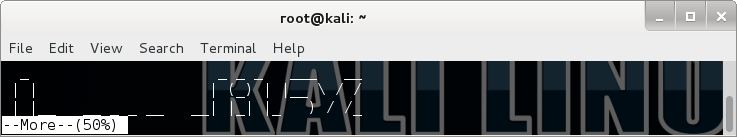

Since I wasn’t sure how to proceed on the bandit system, I tested it on my own box first, by using more on a file large enough to activate it:

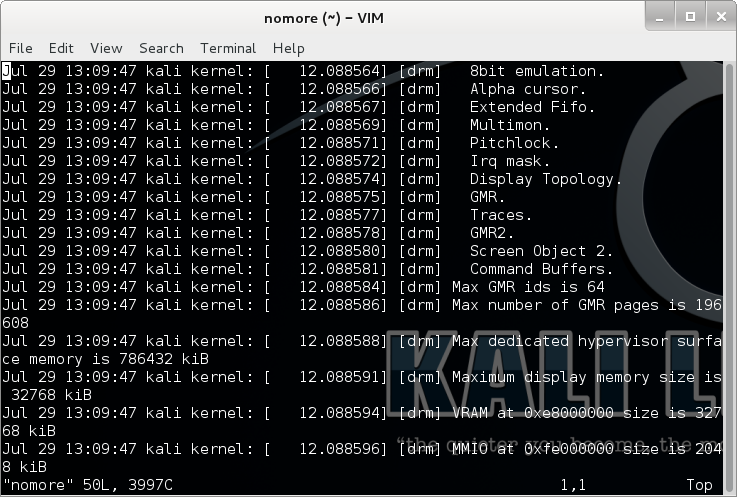

And pressing v dropped me into Vim!

That gives a way to view the file beyond the first screen. But in the login shell, there was no interaction, I couldn’t get more to step in..wouldn’t even have known about it without checking the shell. But when I played around on my box some more, if using more on a very small file, it would just output its contents, the same way as cat, so there would be no indication that more was used to display it. Just like via SSH! So it means that text.txt file doesn’t really have anything than that bandit ASCII art. But I wanted to check, and wasn’t sure how to enter into the more prompt by logging in…it turns out that can be done by making the terminal window small!

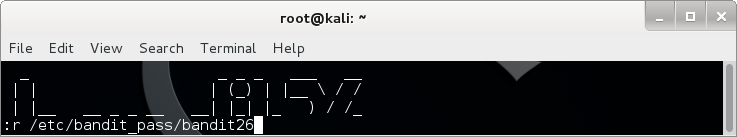

Bingo! From here we can drop in vi! But as expected, there is nothing else in the file. I admit I don’t use vi and the few times I needed to use it for something I had to follow instructions by looking on the internet, so it took me a little more reading before I stumbled upon this very useful SO post. It’s possible to read another file by inserting it into the current file! You can do this by typing :r newfile:

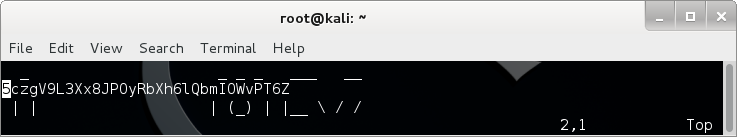

Next I had to scroll through some warnings about multiple swap files, and at the end I saw the password inserted where the cursor was!

So the password is 5czgV9L3Xx8JPOyRbXh6lQbmIOWvPT6Z, and this was a hell of a fun level to complete! :D

Useful command(s)

The /etc/passwd file is a text file that describes user login accounts for the system.

Each line of the file describes a single user, and contains seven colon-separated fields:

name:password:UID:GID:GECOS:directory:shell

shell This is the program to run at login

more is a filter for paging through text one screenful at a time. This version is especially primitive.

Interactive commands for more are based on vi(1).

v Start up an editor at current line. The editor is taken from the environment variable VISUAL if defined, or EDITOR if VISUAL is not defined, or defaults to “vi” if neither VISUAL nor EDITOR is defined.

Level 26 –> Level 27

At this moment, level 27 does not exist yet.

Ok, coming back to this was lots of fun, and 2 more levels have been added since I solved it the first time, so perhaps more will be added in the future as well. The bandit wargame has been one of my favorites, and level 26 was really interesting!